A little longer notes from a musical LH fascist on the interpretation of medieval music. They are for musicians who are somewhat fond of medieval music, but have not yet seriously (and I mean seriously) studied it. So, it is probably for everyone who thinks they will play medieval music (or has even been doing something like that for a while).

Two things brought me to them: Debates with various studied and often great and famous musicians who are used to the generally learned romantic interpretation in our country, and they considered my need to interpret old music authentically funny, because they play „as their beaks grow“.

And the second reason is the number of nice people who play something they consider medieval music, and I suffer from it. And at the moment when we meet, there is no room to explain why I suffer instead of cheering. People around fencing and larp will understand this example: During the nineties, a wave of „keckars“ passed and various historical fencing groups were doing things that were really ridiculous, in ridiculous historically inappropriate costumes with bad replicas of weapons. But that has somehow changed and nowadays (except for beginners) the groups that go to events are mostly nicely dressed, nicely armed, many of them have a bunch of professional texts loaded and many of them set a very high bar for themselves and others. In terms of appearance. This progress has not penetrated the area of what is played as music. From a musical point of view, (almost) only scumbags.

So I have a (perhaps embarrassing) ambition to contribute to getting things moving. So that a medieval band plays medieval and not „medieval“ music. It’s longer, but I think it makes sense not to shorten it.

Notation and its interpretation

When you read the sentence I love you, most of us naturally read it [ajlavjú] – even though there is nothing like that written there. However, most of us know that the text is in English and that’s how the English read it, or interpret it. When we want to read English (and, in fact, the same applies to almost all other languages), we must combine the ability to read letters with knowledge of the interpretative “cipher” of how to read them. A person who reads English text phonetically will come across as comical, we will probably consider him a nutcase – and what’s more, the English will probably not even understand that he is reading them a text in their language.

A similar necessity to combine the ability to read plainly with knowledge of the interpretative “cipher” applies to music. And the older the music we deal with, the greater this necessity is, because the “cipher” of the Baroque, let alone the Renaissance or the Middle Ages, often differs fundamentally from today’s, and interpreting Baroque music notation according to a modern interpretative cipher often means playing diametrically different music, much like the phonetic reading of English.

Why can’t we “trust” the notes and read them “as they are written”? Early music has been passed down through the ages by tradition. When it was written down, it was actually just a „drawing“. Most people who sometimes play music around a campfire or the like will realize that they actually make such a „drawing“ themselves most often. It often has only the text and chord symbols above the text. There is no need to write down the rest, because we know the melody. The notation of music in the oldest medieval manuscripts is often similar – there is only the text and then (instead of chord symbols) symbols indicating the movement of the melody (neumes). And that’s it. There was no need to write down the rest, because it clearly resulted from a living (and at that time easily verifiable) oral tradition.

How the melody was written down, or Ut queant laxis Guido of Arezzo under the microscope

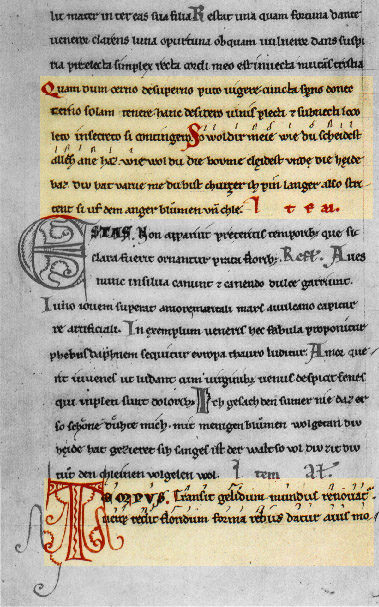

In this hymn, we will show the basic stages of the development of music notation – neumes, mensural notation, musical notation. So first, as Guido wrote it down – neumes from the 11th century:

Neumes were signs written above the text, they looked like hooks, dashes, wavy lines… and marked the movement of the melody. The oldest musical notations in neumes come from Carolingian monasteries from around the year 800. Before that, music was usually not written down at all and was passed down exclusively by oral tradition for centuries. However, older musical notations existed – in our cultural circle, the Greek (later Byzantine) system was used here and there, where each tone was assigned two letters – one for the interval and the other for the rhythmic value. Boëthius also describes them. However, it was a truly academic notation, which was rewritten and developed in theoretical writings, but practically did not spread much – no wonder, it was so complex that its use was complete hell.

Therefore, during the 13th century, the so-called black mensural notation came (for the layman, it may be surprising that it is still used for liturgical singing today):

Mensural notation looks very similar to modern music notation in many ways. (And you can also try comparing it with neumes!) It began to be used during the 11th century. However, you will find a number of differences – the staff has only four lines, rhythmic values are not written down (they are given by tradition and generally binding rules), bars do not exist – instead you will find very irregular phrasing depending mainly on the text.

The double at the beginning of mensural notation prescribes intonation in the 2nd mode. Tonal settlement and intonation the scheme is determined by the combination of the C sign and the tonal mode indicated (sometimes) at the beginning of the composition, which was usually given unambiguously by tradition. The author of the mensural notation was very likely still aware of the living oral tradition, so his transcription is informed and corresponds to the original.

Sometime in the 19th century, a transcription into modern music was created – with all the problems and errors that usually accompanied these transcriptions:

Please note how the author The transcriptionist was not familiar with modal intonation and was not sure whether to write c or cis, a correctly intoned seventh degree sounds somewhere in between. Not to mention the low second and third.

Although this is an otherwise quite successful transcription, it contains another nonsense – bar lines and the need to establish rhythm according to our modern rules. Medieval music was rhythmized completely differently than modern music, the notation usually included some instructions for phrasing and singing breaths, but was essentially never divided into regular bars, as we know them from late Baroque and more recent music. Heavy beats were usually irregular (according to the text), the rhythm itself was usually also irregular and used odd and even beats alternately, etc. Well, as we know, the Romantics of the 19th century overlooked this and even today’s music notation software can’t do it… (At least the version of Sibelius I used a few years ago couldn’t.)

The tempo used to be very brisk (about 120), and when sung in a large choir (for practical reasons) a little slower (today’s Benedictines sing Ut queant laxis almost twice as slow…).

Guido based the solmization system on the text of this song, part of which was a set of signs that he showed to the singers on their hands to indicate – not the movement of the melody, as would correspond to the logic of notation in neumes, but actually the absolute tone. His system is a bit cumbersome for us today, but it served its purpose in its time (if I dare say correctly). It looked like he was pointing with one hand to individual joints of various fingers of the other hand, and these meant individual specific tones. You can see the notation of this system on the right.

Guido based the solmization system on the text of this song, part of which was a set of signs that he showed to the singers on their hands to indicate – not the movement of the melody, as would correspond to the logic of notation in neumes, but actually the absolute tone. His system is a bit cumbersome for us today, but it served its purpose in its time (if I dare say correctly). It looked like he was pointing with one hand to individual joints of various fingers of the other hand, and these meant individual specific tones. You can see the notation of this system on the right.

Medieval notation, with a few exceptions, did not record rhythm. Not because it did not matter, or because all notes were supposed to be the same length. Partly it was simply not necessary, because the rhythm of the song was generally well known, and partly it was not necessary because the rhythmization was subject to generally used rules corresponding to the aesthetic ideal of the time. For example, the notation of the syllables tu-o-o-rum is written in black notation with the sign clic a longua, which results in the rhythm eighth-quarter-eighth-half. Isn’t that there? It is, that’s how this phrase was rhythmized, it’s exactly what Hieronymus de Moravia describes. And let’s look at another mistake in the musical transcription. The black notation after tuorum indicates a vertical line, which is the end of the phrase (because of it the last note of the four is a half note). Jo-an-nes is an eighth note-eighth note-half note-breath and the end of the phrase. And indeed, in both places it is necessary to sing the end of the phrase in a feeling way. The musical notation, which tries tooth and nail to count the bars, has the nearest bar line very far away and if a trained singer sings from these notes, he will phrase the melody completely differently. And pointlessly.

Medieval music – including liturgical music – was very dynamic and rhythmic, even though it often involved irregular or odd rhythms.

Medieval notation (and this was true almost until the late Baroque) did not write ornaments on individual notes, because their specific execution depended on the performer. The medieval musician knew which notes the ornament belonged to and sang it there according to his feeling. For example, a look at the black notation says that on the syllables Sa-a-ncte-e we absolutely need to embellish. It is mandatory, it is clear according to the type of phrase and there is no need to write it down. Let alone write down what ornamentation you will sing there.

A modern interpreter of The same notation is read without embellishments (he has no idea about the “decorative” rules), and the modern composer carefully writes all the embellishments in the music notation. The medieval musician intoned in modes and knew which modes belonged to which compositions and why. His singing therefore had an inimitable charm. The modern singer sings the same notation at the piano and it is colorless and flat. An even greater shock for modern musicians, however, are the melismata, or actually entire melodic phrases inserted into the basic melody according to traditionally given and relatively clear rules.

When I make a leap to such a Vogelveide, and look at his authorial notation of the song, I discover a shocking thing: Only the text is indisputable. The melody is already a matter of interpretation of non-artistic signs. Just look at the page with the notation of his song:

Although we can transcribe this notation quite easily today, let’s admit that even today there are several schools of music historians who differ in their opinions about it. We cannot read the rhythm from them and have to interpolate it from what we know about the musical tradition of his time. We have some material for this and we make such interpolations mainly on the basis of analogies to other music (which we have in parallel also in more modern notations) and with regard to the knowledge of the music theory of the time. Various music historians will again argue frankly about how to do it. When it comes to harmony, bass leading, etc., we know that we know nothing there. Or rather, that nothing of the kind belongs there.

What does this mean? Whoever sings such a minnesäng, and has built a melody based on an analysis of the manuscript, may be singing it well. Whoever uses a ready-made transcription by Vogelveide, of which music textbooks and encyclopedias are full, will almost certainly have the wrong rhythm and phrasing, because these transcriptions, copied thousands of times, were mostly created in the second half of the 19th century and were made by romantic revivalists who respected the original authors only partially and in any case only to the extent of their own knowledge of early music – and this knowledge was quite poor in the 19th century. Anyone who plays a lute (even a Gothic one) to their interpretation of Vogelveide, or adds a tambourine and a flute in the second voice, is already playing their own music, which very likely has little in common with the original text. We know very little about how such harmonization was created, and everything we know tends to suggest that there was none, vertical harmonies were completely outside the aesthetic ideal of the time, and the music was truly monophonic – as is the case with traditional Arab music to this day. When we realize this, we understand that virtually no one plays an authentic interpretation of medieval music today, and that all those “quasi-medieval” bands play thoroughly contemporary music, albeit based on medieval melodies, and play it on (sometimes good, sometimes rather romantic) copies of medieval instruments (but usually modernly strung and tuned). They express themselves completely with the musical means of the twentieth (or twenty-first) century, although they modify them slightly according to the more or less lay ideas they have about early music.

As music became more complex and tradition disappeared, it became necessary to write it down more precisely, and gradually, instead of neum, simple notes (mensural notation) began to be used – which did not yet record the rhythm. Then rhythm notation was added, etc. Although Baroque music already used a musical notation that was almost indistinguishable from modern notation at first glance, it was still true for Baroque music that only what was absolutely necessary was written down. What is clear from tradition or somehow from the principle of the matter does not need to be written down. Thus, even in the Baroque, rhythm notation does not express exactly what we obtain by mechanically using the knowledge of reading modern music, regardless of the fact that Baroque notations do not contain ornaments, which were, on the contrary, very characteristic of the Baroque and about which entire works were written. It was only in the third quarter of the 19th century that some Romantic composers began to demand that their music be written down absolutely accurately and that no one could ever interpret it differently, and so they complicated the notation with a large number of signs and symbols used today (which is not a bad thing), but above all they caused the generally accepted principle that the composer wants the musicians to play exactly what is in the notation. That means – no tradition, no unwritten ornaments, let alone melismas, etc. In short, if we play music older than the mid-19th century without using additional interpretative “ciphers”, we will easily reach the level of those who read English phonetically.

But you don’t have to feel guilty now. This topic is a frequent subject of dispute even with respected professors of music academies, and it must be said to the Prague academies that the attitude still persists there that it is best to play everything „as our beaks grow“, that is, understand romantically. Although everyone knows that we will not grow any beaks, and everything that we have connected with music and musicalm feeling, let alone interpretive skills, is a cultural matter, we have listened to it and someone has laboriously hammered the interpretation into us for years. Among musicians, you have the majority who read English phonetically and claim that it is simply better that way, and the minority who are trying to learn English, even though they make mistakes.

Harmony

So, by the way, what key is that medieval song in? What chords should a player on the cittern, lute or other instrument alternate? Do you know that? That is treason, none. As soon as he starts playing one there, he pushes his musical thinking beyond the boundary that was established at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the Middle Ages, they did not know any chords, they did not play them and their musical thinking did not need them. They did not relate to vertical harmony, but to perfect melody. If it is to be the Middle Ages, and at least a little authentic, forget that there is such a thing as a chord.

Singing – intonation and technique

This is one of the biggest weaknesses of practically everyone who plays „medieval“ music. The more musically educated we are, the more we tend to push the intonation towards well-tempered tuning, which, as everyone knows, was only introduced to the world by Bach in the mid-eighteenth century. In the Middle Ages, intonation was used in modes, and I dedicate a separate article on modal intonation to intonation. Yes, it is terribly difficult for a person who grew up surrounded by modern music.

The second hell is the attempt to introduce any of a number of modern mannerisms into medieval music. It is not baroque opera, it is not at all pra and anything that sounds like „serious music“, or opera, has nothing to do with medieval singing at all. But medieval music does not include mannerisms brought from folk, rock or anything else modern. This is where almost everyone who tries to interpret the Middle Ages from our contemporary Western world fails.

Have you ever heard the organ register „vox humana“ on Baroque and Renaissance organs? When thinking that this technique was used to sing, today’s singers and Western monks run away in horror, because such a bellowing contradicts all our current aesthetic ideals. With the vast majority of those bands, my ears bleed after the first two notes they sing. Because the musically educated make an opera out of it, the musically uneducated make a cauldron. And both are miles apart. On the contrary, in Moravia, you will hear a far more authentic shriek on the dulcimer.

Aesthetic Ideal

Many modern musicians who have studied music suspect that early music was interpreted differently, and that it was even played on differently built and tuned instruments. They have many arguments for not trying for authentic interpretation:

It is clear that by doing so we are entering from an area that we pretend to know, into an area in which we are searching and must openly admit it. It is also clear that early instruments not only had a different sound, but also gave players different interpretative possibilities. In connection with their tuning and construction, they were usually played less loudly. Their tone was usually more full of overtones, but it was quieter, less firm and sustaining. Many technical finesses honed in the 19th and 20th centuries cannot be played on them at all. If I stick to my own instrument – if I compare the lute and the modern guitar – the lute is quieter, I don’t play with the flageolets like I do on the guitar, I only apply some vibrato very slightly and with difficulty, I have less dynamics available because my frets are mostly spread out in some mode (not in equal-tempered tuning), it is a major problem for me to switch to the alto lute in the key of, say, E major. But then there is the other side – on the lute, they can easily play ornaments that a guitarist can only dream of, and because I tune modally, I can play melodies and harmonies that are so distinctive and pure in intonation that a guitarist with equal-tempered tuning has no chance. It is similar with other instruments – modern violin versus baroque violin, let alone Gothic fiddle, cello versus viola da gamba, and I could go on. The truth is simply that if we demand modern playing of modern music from old instruments, we will of course find that modern instruments are much better suited for it. For old music and its technical finesse, it is just the opposite.

If we rewrite a Baroque composition for a symphony orchestra and are aware that we are playing our own modern interpretation of Baroque music, then we can do anything with it and we can tune it however we want. Among famous conductors, this was done by Stokovsky, who completely ignored the original interpretation, built his own (more or less post-Romantic) interpretation and instrumentation of Baroque compositions, and yet it was tasteful. He more or less blatantly made his music using Baroque compositions. He took Bach’s organ fugues and wrote them out for a modern symphony orchestra. It had very little in common with Bach, but strangely enough it sounded good. With less taste and less invention, most conductors do it today. Moreover, the vast majority of them usually have no idea that they are making their own music, and are convinced that they are playing the aforementioned Bach. They refuse to deal with the fact that Bach never sounded like this. And when we talk about medieval music, let’s take it as a fact that 99% of „medieval“ pieces el plays completely modern and inauthentic interpretations from transcriptions made in the 19th century – and therefore full of errors. Authentic medieval music is really rare today and is not even performed by ensembles like Sequentia or Schola gregoriana pragensis D. Eben (although many people think so).

We can try to ask ourselves whether the truth is that even Baroque authors would like to compose for modern instruments and would forgive the players for not being able to decorate at all (which most modern studied players really can’t do at all) in exchange for romantic vibrato. Would they not like to equip them with modern instruments… Such is a frequent argument against authentic interpretation. It is stated that the Baroque orchestra sounded completely different, but that was a mere virtue out of necessity and a Baroque composer would jump for joy if he heard his compositions interpreted in a modern way on modern instruments.

Well, he probably didn’t. We could also say about Chaplin that he only made silent black-and-white grotesques as a virtue out of necessity, and if he could, he would have made them as 3D color films with Dolby stereo sound. If master Theodorich had a digital camera and Photoshop, he would not have played with plate paintings and would have made a gallery for Karlštejn on his computer… Of course, this is nonsense. If someone reconstructed what the models from which Theodorich painted his saints looked like, and created a perfect „photographic“ image of them taking into account our contemporary artistic knowledge, we would probably not be interested in these reconstructions at all. Theodorich’s paintings fascinate us precisely because they are able to relatively faithfully convey the vision of the world and emotions of their creator. It is evident in the paintings that we are not interested in their modern „interpretation“ of old paintings, but precisely in the insight into the perception of their creators. And so does a perceptive and educated listener of early music. He cannot simply rewrite it with the arrogance of the director of an American „historical“ blockbuster. It is an opportunity for him to discover other dimensions of music. And then – even if the old authors approached it that way, history is simply different. Chaplin became famous for his silent slapstick and Bach wrote his music as he wrote it. If it were not for the era of silent film, Chaplin might not have made any films at all, because the expressive possibilities of modern film would have been lost to his talent and interest. A modern interpretation of old music is comparable to someone taking modern film instruments, Chaplin’s script and making new Chaplin slapsticks today. They will be colorful, stereo sounding, full of action, the camera and editing will be more dynamic… but the result will be a depersonalized kitsch claiming to be Chaplin’s work – the magic will be gone, at least for me.

Like a medieval fiddle strung with gut strings and authentically tuned, the sound moves more between a saxophone and an ungreased door than having anything in common with the sound of a modern violin. And a medieval listener would probably be shocked by modern violinists with their vibrato.

There is another aspect, unique to music: While to perceive the panel paintings of Master Theodoric, it is enough to go to Karlštejn and look at them there, to perceive the music written by ancient authors in retrospect, you need a performer who plays it again for us, or reconstructs it. This is completely specific to music – it lives only in the fleeting moment when it is played. There is no recording of Vogelveide, if we want to hear him, it is not enough to go somewhere and look there, someone has to study what the music looked like and try to perform it.

The second reason why I think he would not jump for joy is that the modern musician and listener relies too much on his own taste and his own – that is, modern – aesthetic standards. The perception of beauty and ugliness is influenced by our upbringing and the world around us. Today we have expectations that music either fulfills or fails to fulfill. Every day we see people a generation older or younger listening enthusiastically to music that we find imperfect, ugly – and far removed from the ideal of beauty. The brass band that our grandfathers loved is almost a symbol of pseudo-musical farce for our generation. And we don’t realize that in the case of the Baroque or even the Middle Ages this shift in standards is infinitely greater.

To a modern violinist, a medieval fiddle sounds more like an offensive weapon than a musical instrument. But a medieval listener would probably be completely disgusted by the virtuoso – however shallow in his eyes – playing of a modern violinist with a modern instrument. The abyssal difference in the perception of the ideal is continuous, for example, in singing. If we hear modern opera singing, a significant part of the audience turns away in disgust, many children laugh. When we listen to opera recordings from the first half of the 20th century, for many of us they are no longer acceptable except as a statement of contemporary interpretative opinion. This entire opera technique, which is taught in European music schools, is absolutely unnatural and originated in the 1840s in the Milan opera house as a solution to the purely technical problem of how to make a singer able to sing in such a large hall – and often in positions that are not suitable for him are natural. The first performances of these – at that time hypermodern – singers were accompanied by passionate discussions and ridicule from many contemporary music critics. But the new technique took hold because it fulfilled the purpose of handling a huge hall – and the romantic megalomaniac composers longed for monstrous operas, large orchestras and large halls.

A baroque singer would certainly condemn modern opera as aesthetically unsatisfactory. The singing has too distorted vocals, the breathing is too unnatural, the head tone is worthy of a eunuch and that terrible and ridiculous vibrato… And an older singer would probably be even more critical. The tempered intonation according to the piano is completely false, no one knows how to embellish, no one knows how to use a straight tone full of overtones.

Simply put, aesthetic opinion is not the same as technological sophistication. Only a self-centered narcissist can think that his aesthetic opinion is the best of all and that the fact that others have a different one is only because they have not yet understood his. The aesthetic ideal of a Baroque or Medieval composer was no less advanced than ours. He was simply different. These people had a different philosophy and a completely different scale of values. They lived a different life and in different conditions. The concept of beauty had a different content for them. It is nonsense to think about how Bach would have handled modern instruments. The only true thing is to take note that he had his own aesthetic values and composed his music according to them.

Early music expresses many meanings that escape us today because we have no idea of their meaning. A small example: When someone today wants to write „old-sounding“ film music, he leads in harmony in C minor and modulates the final notes of the phrases to C major. Why? It sounds „somehow“ baroque. Many spiritual Baroque compositions end in A major. – So not in C or G, it is in principle A major – and this regardless of the key of the whole composition. Because A major has three crosses – turning attention to Christ. And this anagram of thought is foreign to today’s man. At the same time, old music is full of similar meanings hidden for modern man (and perhaps „secondary“ for the modern listener) – which, however, were important from the point of view of the aesthetic ideal of the Baroque man. A modern violinist would easily transpose such a composition, adjust it, rework the phrasing. He would destroy all these meanings, just so that he could play the composition with a more virtuoso technique. A modern listener would not recognize it, Bach’s contemporary would probably perceive it as a degradation of the composition, regardless of the virtuosity of the player.

Bridges to medieval music

To avoid the feeling that I am a scoundrel: I like it when I come to a castle and someone is playing there, it is a perfect atmosphere booster. I absolutely respect these quasi-middle ages as bridges – the first meeting that will eventually lead to starting a search for the real Middle Ages.

The first bridge for many people is often various „chorales“ – „medieval“ sacred music to be precise. And I will name their greatest protagonists right away – the Benedictine monks from Silos. They made this music famous in the 20th century, sold millions of records, and contributed to interest in the Middle Ages. But do they sing the Middle Ages? Not by mistake. They do sing sacred songs, of course originating from medieval collections, but it is definitely not about reconstructing their medieval text. So that it does not seem like I am slandering them – it does not even occur to them that such a thing should be the case. They sing songs for the needs of their liturgy. It is a completely modern liturgy, let us remember that it has undergone several church reforms since the Middle Ages. And it is a completely modern way of singing. It is beautiful, I agree. But let’s not live under the illusion that we hear the same thing as in the Middle Ages. If we wanted to make at least a small excursion into the Middle Ages, we should rather head to the Middle East to a mosque, to a Greek church in the Balkans, or at least to a synagogue on Saturday.

The medieval liturgy was not at all like ours, and what was heard in it, you would hardly classify as „ambient“ in a CD store. It was very lively, emotional, at a very fast pace, and until the 13th century it was common to dance and play drums during it, because several drummers were a common occurrence in the church. On the other hand, the organist only began to appear there from about the 16th century. No melodic instrument simply belonged in the church. The liturgy is the descent of God’s spirit through the voices of the faithful and priests, any melodic instrument will spoil it and its tones will interfere between God and the faithful.

Ensemble Organum. It’s a bit younger, 15th century. Unfortunately modern intonation. But it has its charm. No ambient singing.

And now we’re going against the flow of time:

This is a tasteful example. It’s emotional, it’s nice to listen to. For a medieval liturgy, it’s very slow and high. They would choose such a tempo for a big feast with a large choir. The tempo should be much higher. Of course, I have a complaint about the modern intonation. The combination of a female cantor and a male choir sounds good to me. But that’s the aesthetics of the 21st century. In a medieval liturgy, this would be very difficult. Female cantor > female drone. Kantor > male drone. As I write, it’s a nice liturgy for the 21st century.

In the Middle Ages, a female choir on a major holiday would sound more like this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uesAy3mb97c

And here is the entire Coptic service. Journey to the Middle Ages. So until the 14th century, you probably heard the service in our church something like this. We in Europe have already forgotten it. The Copts have kept the tradition intact.

What to listen to and what not to listen to?

There are many music historians who go to the Benedictines in Silos (or other famous monasteries) to learn their liturgical singing (in layman’s terms, „chorales“). After all, the monks in Silos themselves have released several CDs that have sold several million copies under the label of a can of medieval music. Unfortunately, this trend, which froze somewhere in the eighties and nineties, is still the one that prevails in the academic sphere among music historians, not to mention, for example, HAMU, where attempts at authentic interpretation of old (meaning baroque and older) music are still perceived as something strange. Although these academic relics have little in common with medieval music.

All (that is, in our Western church circle, almost) today’s religious primarily perform liturgical ceremonies according to current liturgical rules, which include, from their point of view, completely secondary music. And the last significant change in liturgical rules was codified at the Second Vatican Council at the beginning of the twentieth century. It responded to the great real changes that took place in the nineteenth century. From this time comes the form of liturgical singing that we could describe as „angelic singing“ – the long, kind singing of genderless angels floating far beyond this world. At the end of the 20th century, this form of liturgical music merged perfectly with the musical wave of ambient music. But that is the liturgy of the early 20th century.

The previous significant church reform that completely changed the form of the liturgy – and therefore also liturgical music – was made at the Council of Trent in the middle of the sixteenth century. It directed liturgical music into a spectacular and effective form, coherent with the recatholicization policy of the church of that time. But even that did not respond to medieval music, it responded to the vocal polyphony that emerged from the ars nova. And the intricate music of the ars nova – as an essence we can cite Machaut’s mass – was still far removed from the medieval liturgy.

Medieval liturgy is thus hidden in time until before the emergence of the ars nova and therefore sometime before the end of the 13th century. The contemporary Benedictines and other congregations do not even hint at trying to return to this form of liturgy and liturgical music (and why should they), they continue to develop – and it is actually a coincidence that the form of their liturgical singing corresponds to the modern person’s idea of how he would like to hear the medieval liturgy. If we want to reconstruct medieval liturgical music, it is best to ignore this modern experience and stick to the real sources.

Apart from written sources, which we will return to elsewhere, it is mainly about the tradition of early Christianity. We know that there are some churches that maintain this tradition very tenaciously and orthodoxly. We also know that early Christianity was greatly influenced by the Jewish world and Egypt, because Christianity spread to the large Egyptian cities first. Given that the Jews also carefully maintain their tradition, one of the sources of ideas about early medieval liturgical music is listening to contemporary Jewish worship. So if you really want to deal with medieval music and not just the modern misconception about it, go to the synagogue on Saturday to listen, it is instructive. Or go to the Church of the Holy Spirit in Prague sometime, where Armenian services are held on Sundays.

Another excellent source is the aforementioned early Christian and Orthodox churches. You can find a lot of Greek liturgy on YouTube. (# greek liturgy, byzantine liturgy, orthodox liturgy, armenian liturgy, coptic liturgy…) It is worth listening to both for the singing technique and for the intonation. Listen to Agni Parthene by this choir.

Let’s take the Syrians, or especially the Coptic Church. The Coptic Church lives in monasteries that are almost airtightly closed off from the outside world – and has done so for the entire previous two thousand years. The resolutions of the Council of Nicaea in 325 seemed to the Copts in many ways as an excessive departure from the original ideals and they rejected them as heresy. So we know almost reliably about the Coptic liturgy that it has preserved its tradition as a constant, unchanging one since the 4th century. At the end of the 20th century, however, Coptic monks began to do something completely new and fascinating. Some of them, after many years in monasteries in the desert, systematically go to large cities in small groups and try to spread this original faith with the original liturgy, and what is more, they continuously record their services in *.mp3 (nowadays on video) and place them on the Internet. On the website of the Coptic Church, you can find the essence of the early Middle age eternal liturgy.

We also know that when the Arabs occupied the territories that had previously belonged to Byzantium, they readily adopted Roman culture – including music. And unlike the European West, they did not subject this music to any revolutionary development, but more or less faithfully preserved it. The Arab muezzin sings today just as he did thirteen centuries ago and almost exactly as a Christian priest or monk sang at that time. If we hear today’s dervishes singing, we can easily imagine a medieval European monk in their place – in terms of phrasing, tempo or intonation, they are a treasury of medieval music. If we analyze traditional Arab music, we even find that the Arabs – and it is said that the Syrians are the best of them – still intonate in modes, and that the tradition of several dozen modal keys is still alive in the Arab world. Let us take it as a fact that if we want to sing medieval music faithfully and intonate it as medieval singers intonate it, the Arabs are our best teachers.

Of course, there is another tradition – and that is the living tradition of the Eastern Churches, especially the Greek (and Armenian) Churches. The Eastern Churches have already undergone some development, however, even this was far less than the development in the West and in the Greek monasteries we can still hear liturgical music very similar to the liturgical music that sounded in the Middle Ages in the monasteries of Western Europe. We know that at the time of the Great Schism, in 1054, the liturgy was completely common and we have many documents that show that even in the 12th century there were almost no differences. That is, including liturgical singing – and liturgical singing was the ideal for court singing and the singing of troubadours. Then the West went in a different direction – the Parisian school of Notre Dame was founded, etc.

And here’s a slightly different example.

Ensemble organum is one of those who sing the old liturgy quite tastefully. That is, except for the tuning. This Byzantine example is closer to medieval reality: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Q8i0CYs-CM

Revived castles and medieval bands

Another bridge is the various „medieval“ bands at various festivals, medieval pubs, etc. They are also a long way from medieval music. What do they play? Well, in part, it is truly medieval music, but in the vast majority of cases it is from sheet music transcriptions made by national revivalists in the second half of the 19th century. And they, because they did not know much about the subject themselves, transcribed it completely, I would say, loosely. In half of the cases, the rhythm and phrasing do not even resemble the critical transcription that we can read from authentic materials today. In a large number of cases, they play music whose non-medieval origin they have no idea about. It is quite common to mix songs from the 16th-18th centuries, and in some cases – especially when it comes to the German Middle Ages – these are completely modern melodies written to a compilation of original texts (from which the melody has not survived). Who would swear to the originality of the Scottish song about two ravens. The truth is that the text is a compilation that G. Byron composed from fragments of medieval texts and „provided“ it with a tune from the early 18th century. Half of the „medieval“ bands have it in their repertoire.

I’m not talking about the fact that they have no idea about embellishments, melismas and other singing finesses that were not written down until the 19th century, because they were based on tradition and complex interpretation rules – which were as natural to a medieval musician as they were distant to a modern one.

What do such bands play on? Does it have metal strings, frets hammered into the fingerboard…? Yes, strings from the 16th century and frets from the 19th century.

Do they start the song with a beautiful, mournful D minor? That was a key typical of the Middle Ages, wasn’t it? Really difficult. Harmonic harmony, a chord, was not recognized by European music until the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries (and non-European music only absorbed it in the 20th century under our influence). Any chordal playing in medieval music is complete nonsense. Just as they did not know minor or major keys. They used dozens (the most common were the first 8) of tonal modes, which were based on natural tuning and again very subtly strengthened the effects of the melody.

Tonal space, tuning, that separates us from medieval music by miles. The modern layman (and most musicians, as laymen) has no doubt about how to tune: After all, we have tuning forks, pianos… Oh! Everything is wrong. All these conveniences take into account tempered tuning, which, as we know, originated in the 18th century. The strange thing is that all intervals are the same distance from each other in it, it can be transposed – and on the other hand, all intervals except octaves are false. Some of them are unbearable. A medieval musician would have driven us with pitchforks for tempered tuning. (For those curious, I recommend the previous article on modal tuning.

That a layman wouldn’t recognize it? But of course he would! If you listen to the muezzin calling to prayer, it will be clear to you that this is not our tonal system. In the Middle East, people still feel music in the old tonal modes. Their music has not gone the way ours has. But, if we are talking about the Middle Ages, they are a thousand times closer.

So what to do and what not to do with medieval music

Medieval music should be played by people who know it and can play (sing) it. It is not enough to be a good (and perhaps even a trained) musician who thinks musically in the 21st century. Medieval music is a trip to another world, another way of thinking, another aesthetic ideal. It’s not enough to find a romantic transcription of a medieval song, it takes courage to give up the „certainty“ of your ideas about what medieval music is and try to find the real one.

For the band that plays medieval junk, this means:

- Throw away instruments with hammered frets and modern tuning machines. And of course, throw away metal strings. An authentic instrument has a different sound. Gut strings are unmistakable. Modernly spaced frets are hell in terms of tuning.

- Throw away romantic musical transcriptions of famous songs. (By the way, when searching for original sources, you will discover a terrible thing: Half of what you have played so far as „the Middle Ages“ is something very young. Roughly eighteenth-nineteenth century. Delve into the original sources – Cantigas, Red book (Libre Vermel), Manuscript of Faenza and many others), get hold of hitmakers like Machaut, Landini, Dufay and others – and you will discover with enthusiasm that there are heaps of beautiful songs that you have not heard of before. Try to practice them in thoughtful and if possible authentic phrasing, if you learn a song from another band’s album, it will almost certainly be wrong.

- Forget about chords and harmony. Polyphony – and polyphonic – came in the 14th century, and until the 16th century, it was practically exclusively vocal, while harmonic (thinking in vertical contexts) was practiced at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. Medieval music does not know it. There is melody (cantus firmus), something rhythmic, here and there a drone, here and there a parallel voice.

- Read something about medieval musical aesthetics. I love In Extremo. It’s great big beat. They have nothing to do with the Middle Ages at all. Well, something – butchered melodies of songs, and some of the medieval ones they invented. They make their own theater out of the Middle Ages. It’s great. But it’s not the Middle Ages.

- In a pub or at the market, different music was played and on different instruments than in noble society. You can’t take a lute or any other similar instrument to the market. The market includes wind instruments, drums, bagpipes. And singing. Yes, bagpipes were played, sometimes even in noble society. Because the medieval ones looked completely different from the ones you know. They were quieter and simpler, until the 14th century without drones, which seem to us to be an inherent part of the sound of bagpipes. They were played on a niner. Just be careful – most of today’s niner players play a baroque niner, which looks different and has a different sound. And so on. If you play at markets, fairs and courtyards, simply forget about stringed instruments. The medieval ones, with the exception of the niner, do not belong there.

- And when you have mastered all that, try to start worrying about the correct intonation. By this I mean medieval modal.

- Don’t give up. You don’t have to make all the changes right away. You just have to start. It’s a long journey and a long search. You’ll see the joy when you realize in a few years what a long way you’ve come since today. (I’m not an arrogant prick who wants to belittle everything you’ve done so far, I just want to shine a little light into the darkness where you can find something nice 🙂

Yes, you can curse me for that. Or go to article about modal intonation.

And here’s the inspiration. It’s closer to the European Middle Ages than anything that haunts our „medieval“ bands:

PS. The article was written sometime around 2005 and please excuse any typos and various ghosts caused by moving to a different platform.